Canadian government has stopped accepting LGBT Iranian refugees to prioritize Syrian refugees

By Dylan C Robertson Feb 03, 2017, 7:44 PM EST

By Dylan C Robertson Feb 03, 2017, 7:44 PM EST

Resource: dailyxtra.com

Mitra’s sanctuary is a mouldy basement in Turkey’s conservative heartland. The microbiology student’s life in northern Iran came crashing down in the summer of 2014, when she was outed as a lesbian. A neighbour beat Mitra, and her parents disowned her. Like thousands of LGBT Iranians, she fled to Turkey.

The 27-year-old now works 14-hour shifts standing upright at a textile factory, before coming home to her transgender partner. The two women sleep on a folding sofa; they have just one plastic chair.

Canada invited both to start a new life 14 months ago, when embassy staff in Turkey started a third-country resettlement application. But our country has now closed its doors, effectively suspending an informal program known worldwide for bringing scores of queer Iranians to safety.

Over the past decade, hundreds of LGBT Iranians have come to Canada, mostly through UN resettlement. But this humanitarian pipeline has dried up as Canadian officials in Turkey focus their resources on bringing Syrians to Canada.

Instead of welcoming them here, Canada has told LGBT Iranians like Mitra to try moving to the US, which President Donald Trump recently closed to all refugees, as well as to Iranians already holding visas.

Many refugees took the advice, and are now languishing in Turkey, unsure whether to try and wait out the US administration or apply to Canada, knowing that they will be sent to the back of line.

“My life is in danger; I can’t go back. If I could, I would. But I can’t,” says Mitra, who agreed to speak with Xtra under a pseudonym. “I’m not Turkish, because I can’t work and study here. I’m nobody.”

A famed program

In late 2010, the government of former prime minister Stephen Harper made LGBT Iranians a priority for resettlement, asking the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) to refer to Canada any Iranians in Turkey fleeing persecution on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Howard Anglin recalls the program starting just before becoming chief of staff to former immigration minister Jason Kenney in January 2011. “It’s obvious that their lives are in imminent peril in Iran,” Anglin tells Xtra.

Canada allowed in roughly a hundred LGBT Iranians between 2009 and 2012, and doubled that rate by mid-2014. They were welcomed by volunteer groups in Toronto, which is home to one of the world’s largest Iranian diasporas. Using their contacts abroad, the groups could refer embassy staff in Turkey to some of the most vulnerable LGBT Iranians.

Arsham Parsi, founder of the Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees, says his group has resettled approximately 1,000 refugees between 2005 and 2015. But the rate of successful applications has slowed to a trickle.

“I was under the impression that by having the Liberal government, they would expand it more and more. But they shrank it,” he says.

In recent years, Parsi says, three or four LGBT Iranians arrived in Toronto monthly. “But it’s been more than 18 months when no one came to Canada,” he says, except for three privately sponsored refugees.

Arsham Parsi, founder and executive director of the Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees.

Arshy Mann/Daily Xtra

Saghi Ghahraman, co-founder of the Iranian Queer Organization, recalls regular contact with the former immigration minister’s office. Since 2007, the group has helped roughly 100 LGBT Iranians make it to Canada and the US, all through UNHCR resettlement.

Getting them to Canada took roughly 12 to 18 months in total, sometimes with her helping Iranians to file affidavits about their situation. But within weeks of the Liberals taking office in November 2015, Ghahraman says wait times ballooned. By February, when the Syrian resettlement was in its heyday, applications hit a total standstill.

“Now, we don’t have any contact, and nobody answers us,” Ghahraman says.

A spokesperson for Canada’s immigration ministry told Xtra it doesn’t categorize refugees as LGBT, and can only provide a processing timeframe that “is an average based on the last 12 months” which “may not reflect the correct processing time for new applications.”

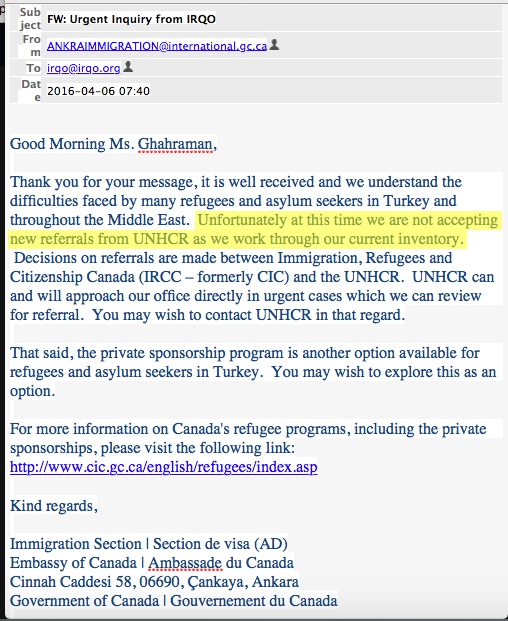

Ghahraman says she made multiple calls to the immigration ministry, the UNHCR and consular officials. In an April 6, 2016, email she provided to Xtra, Canada’s embassy in Ankara confirmed to Ghahraman they weren’t taking any more LGBT refugees.

The email from Canada’s embassy in Ankara, Turkey.

Provided by Saghi Ghahraman

“Unfortunately at this time we are not accepting new referrals from UNHCR as we work through our current inventory,” the email says. “That said, the private sponsorship program is another option available for refugees and asylum seekers in Turkey. You may wish to explore this as an option.”

Ghahraman says she’s scrambled to find churches and community groups in Toronto that would offer to help. “I looked everywhere I could; called the churches, everywhere that I thought maybe are able to take LGBT refugees. But they are all exhausted by Syrian refugees.”

She’s also appealed to Ali Ehsassi, the Liberal MP for Willowdale, who asked the immigration department to intervene.

“Nobody is telling us what’s happening now,” she said. “It’s like a game.”

In a Feb 3, 2017, email to Xtra, immigration ministry spokesperson Jennifer Bourque says bureaucrats follow targets outlined for the calendar year.

“Canada has never stopped processing resettlement applications for other refugee populations,” she says. “If Canada had received sufficient cases to meet its targets, then the UNHCR would have offered the refugees resettlement to another country.”

Referred to the US

Canadian embassy staff abruptly ended Mitra’s resettlement application in September 2016. After 14 months of forms and scheduling health checks, they called Mitra to say they were cancelling the claims made by her and her partner.

“They rejected us. They told us they don’t take any Iranians; they only take Syrians,” Mitra recalls. “They told us that ‘if you want to come to Canada, you need to wait until 2018, and at that time it’s not for sure that you will come.’”

On their advice, Mitra switched her UNHCR application to the US. After four months of a new process with American officials, they scheduled her final interview for February.

But Trump signed an executive order on Jan 27, barring citizens of Iran and six other Muslim-majority countries from entering the US, including those already granted visas. The so-called ‘Muslim ban’ also includes restrictions on refugees, with exemptions for religious minorities.

“What kind of justice is this? We ran away from a Muslim country,” Mitra says. “Our families are ashamed of us.”

The federal government has refused to change its intake of refugees in light of the new restrictions. “We are doing our part as a country to meet our global obligations to refugees,” Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen told reporters Jan 29. “We will continue that tradition and we will continue to make sure that we’re open to those who are seeking sanctuary.”

These comments ring hollow to Mitra, who still dreams of a new life in Africa, Asia or North America — in any country where she and her partner can feel safe, regardless of the country’s living standard. “Just somewhere we can study and live as a human.”

“If any country accepts us, it would be showing mercy on us,” she says. “I don’t think Canadian or the US government will do this right now.”

Safety concerns

Hundreds, likely thousands, of LGBT Iranians have claimed refugee status in Turkey, where they can travel without a visa. But the country itself puts LGBT people at risk.

At a clothing factory in the southwest city of Denizli, Mitra works alongside other Iranians. Some have noticed gay or trans colleagues and had them fired. “Turkish people believe that if an LGBT person works for them, their work will not be halal,” she says, using the Muslim term for permissible.

Mitra’s partner only leaves the house to accompany her to their weekly registration check at the local police office. That leaves Mitra working to pay for the electricity, food and rent it takes to live in squalor. Neither have health insurance.

“I want Canadians to know that we are not useless people. We went to university in our home country. It’s not like that will we go to a third country and not work and be a burden to them. We are hard-working people — if we weren’t we couldn’t stay here.”

Mitra, an Iranian lesbian living in Denizli, Turkey, provided photos of the squalid basement she shares with her partner.

Courtesy Mitra

But Mitra worries about her partner falling into depression from the isolation.

Since arriving, three of Mitra’s friends have killed themselves. Others have been raped. Those with enough money have paid smugglers to reach Europe. Ghahraman claims that ever since a faction of the Turkish army attempted a coup d’état in July 2016, one gay man was knifed to death and two lesbians were gang-raped.

“They’re ill; they’re living in the streets,” Ghahraman says. “We have people there that really can’t get out of their house, for fear that their neighbours might attack hem. And the attacks have been much worse ever since the coup.”

Xtra cannot verify these claims, though they have been echoed by other groups. A Jan 25 report by the Asylum Research Consultancy notes that “following the coup attempt, room for dissent is further under threat, including for LGBT persons.” The report cites the August 2016 discovery of a trans woman’s burned body, a gay Syrian’s decapitation in Istanbul that same month and restrictions on civil society.

Ghahraman says she’s in touch with 300 Iranians in Turkey, some of whom have AIDS or cancer. One sold his kidney to afford to live in Turkey, and his health is declining. She knows of 30 people who have been turned away by the Canadian embassy.

To her, it’s a sharp contrast to the image Canada cultivated through the program, gaining international praise as “a maple syrup Mecca for Iran’s gays.”

“It’s tragedy. It’s not what you see in the papers; it’s not those very well-dressed and very good-looking men who are happy and laughing and now getting off at the airport. It’s terrible.”

A trade-off

Though he worked under the Conservative government, Anglin is quick to praise the Liberals’ Syrian airlift. “This was a very good and very well-functioning, and much needed, refugee-resettlement program.”

Anglin says any focus on specific refugees will cause trade-offs, even when digitized records allow other embassies to process paperwork.

“When you prioritize one type of anything in immigration, whether it’s certain type of refugees, refugees overall . . . it has a crowding out effect,” he says. “It will almost certainly have a knock-on effect of — if not excluding at least delaying — other types of refugees.”

Still, Parsi says the government should have put more resources in place. “It’s unfair that in order to help a group of people to put another group of people’s life on hold,” he says.

Parsi claims he’s heard the the Canadian embassy in Ankara had just two staff processing 1,100 resettlement cases a year, a number that has gone up six-fold. He claims that at a meeting with UNHCR officials last November, they asked him to tell LGBT Iranians to apply to the US.

“They said Canada is full; they cannot submit new cases,” Parsi says. The UNHCR “asked us to talk to them and convince them that the United States is a good option and a faster option.”

Now, Parsi says the refugees like Mitra face confusion at the US embassy, rushed demands for exit permits for Turkey and cancelled flights. “Everything is kind of in chaos.”